Last week’s Humanity Vigil in New Haven was restorative, and as far as I know, only the New Haven Independent covered it, though with their competent and thoughtful reporting, it may be for the best that this is as much ink as the event received.

The organizers of this event sent a clear message in advance: “Political action should not be left in the reactionary, separating nature that is demanded by the inner logic of war” and “We decided to stand together, share our mourning, fears and hopes, and speak against the violence and the war, and towards a future of shared life in equality and dignity for all.”

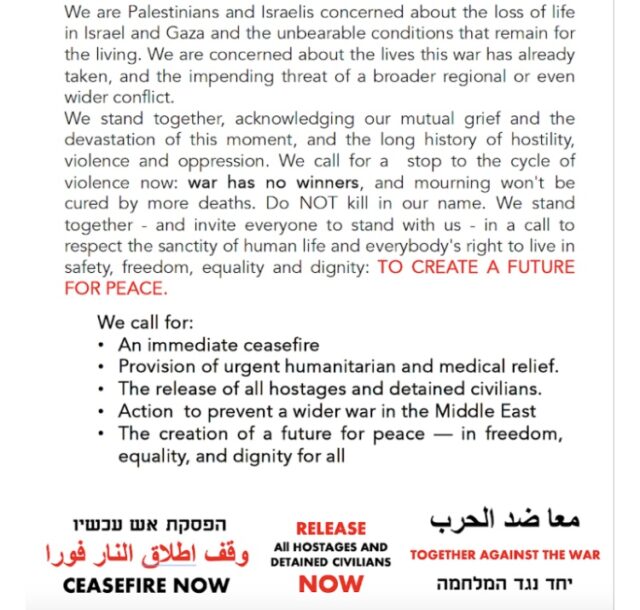

This was their promotional flyer:

What drew me to make the trip was this detail: “There will be no flags.”

Had I the time for another project, I might be tempted to create a podcast called “Fun With No Flags” with episodes devoted to how national flags stoke nationalism. For now, I offer this: waving a flag is choosing up sides in a war, and nobody wins a war. What might begin innocently as a show of solidarity quickly morphs into something else — a slide into rhetoric that harms rather than helps. Country flags become symbols of hatred, halting conversation.

It was a man literally wrapped in the flag of Israel who used antisemitic speech toward me directly in front of Hartford’s City Hall a few months ago following a public hearing.

Removing flags from an environment erases, temporarily, some of our tl;dr culture. It forces long form. It requires conversation, listening, real attempts at understanding. It snaps people out of thinking and speaking in tweets or sound bites.

Dropping cheap symbolism — that includes but is not limited to national flags — means having to step it up and learn how to articulate our complex feelings and thoughts. I know people who have said they don’t feel right addressing the antisemitism present following October 7th because they see that like centering themselves at a time when the focus should be on stopping a genocide.

There are seasoned voices in the mix, though not nearly enough, who seem influenced by the core of improv: yes, and. Yes, we have to stop the aggression against civilians, and we have to acknowledge that there are people calling for a ceasefire who have said absolutely antisemitic remarks; here, I don’t mean the ambiguous “river to the sea” statement that bends depending on context and speaker, but actual, no-doubt-about-it antisemitism that I need not repeat.

There are other voices able to hold many truths and say this: “we have to be very careful not to dismiss or discredit an entire movement because of its worst elements.”

I understand, on some level, why some people might lean into oversimplified belief systems and symbols. They have more company in those spaces. They might feel less lonely not having to stand alone, which happens often when one rejects what they know is incorrect. At the end of the day, how comfortable are they feeling with their choices? I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to equate flags with gang colors. The mentality of wanting to belong is about the same. People will turn a blind eye to remain part of a group. People are terrified of being shunned.

The secret is that there are others out there who defy this lazy categorization. You just have to look for the others, or, as the organizers of last week’s vigil did, let some folks know that they were hoping to connect, and then stand on the Yale campus holding a sign that simply read “Humanity Vigil.”

The signs distributed to those who wanted them were often in multiple languages, not calling for dominance but collective liberation. They acknowledged the shared humanity.

The group formed a circle, looking at one another, and then began to address one another. There was no yelling at anyone. Without amplification, people spoke about why they were there and what they had been feeling since October 7th (or before). There wasn’t the slick dispensing of slogans or anything showy. There was sincerity, an understanding of what was at stake, and moral clarity. The organizers made it clear in advance and several times at the event that this vigil was not in opposition to the nearby gathering replete with flags — this was a different approach, and anyway, this had been planned a week before pro-Palestinian students began gathering at this new location, having been removed from Beinecke Plaza. Some who had been at that other rally tucked their flags in their bags and came over to join.

When someone new entered the circle, I often could not make guesses as to what their background or beliefs might be. I had to stop to pay attention. I had to listen and make an attempt to understand.

This approach erodes gang mentality. It encourages nuance.

The Humanity Vigil was happening right by a pro-Palestinian protest which got loud at times, but for the most part could have been mistaken at a distance for college kids sunning themselves on the quad. When I arrived before the vigil, I walked around and observed a few people quietly and studiously making chalk art. Someone was playing an acoustic guitar and singing. There was a table of food. I saw artwork reading “books not bombs” and was disappointed to see this was a political statement and not a sign for a table of free books. A bit later a speaker arrived and there was about half an hour of noisiness coming from the quad. Then, it quieted down again. This particular space at this particular time did not feel off in its vibes. It wasn’t threatening on a personal level, though perhaps the administration viewed it as a different kind of threat: this is the time of year for campus tours, and several were walking through the area while students were chanting. College administrations aren’t thinking so much, though, about how the way they manage student speech and expression may impact a prospective student’s decision. Had I a child ready to enter college, I would be steering them away from institutions that send in police who assault young people.

Different tactics lead to different outcomes. Whether they know or would ever admit to it, this generation is modeling sit-ins off of the Baby Boomers anti-Vietnam actions. There’s room for discussion about if any of that proved impactful, historically. As I see it, these college actions may get universities to disclose their investments. Students are consumers and have a right to ask where the money goes. Will students be successful in reaching the goal of divestment? Maybe? Maybe, if they understand their role as consumer and having the right to spend their money (or parents’ money or borrowed money) elsewhere.

Will this lead to the kind of future we want?

That’s where actions like the Humanity Vigil come into play. We have to know how to talk to one another and how to listen. How do we expect world “leaders” to have mature negotiations with one another when our own current atmosphere is not encouraging it? Just as when trying to tackle climate change, a whole range of actions are needed, so they are here, but not every action has the same result and we have to think holistically about the futures we want.

Creating a Future for Peace

Last week’s Humanity Vigil in New Haven was restorative, and as far as I know, only the New Haven Independent covered it, though with their competent and thoughtful reporting, it may be for the best that this is as much ink as the event received.

The organizers of this event sent a clear message in advance: “Political action should not be left in the reactionary, separating nature that is demanded by the inner logic of war” and “We decided to stand together, share our mourning, fears and hopes, and speak against the violence and the war, and towards a future of shared life in equality and dignity for all.”

This was their promotional flyer:

What drew me to make the trip was this detail: “There will be no flags.”

Had I the time for another project, I might be tempted to create a podcast called “Fun With No Flags” with episodes devoted to how national flags stoke nationalism. For now, I offer this: waving a flag is choosing up sides in a war, and nobody wins a war. What might begin innocently as a show of solidarity quickly morphs into something else — a slide into rhetoric that harms rather than helps. Country flags become symbols of hatred, halting conversation.

It was a man literally wrapped in the flag of Israel who used antisemitic speech toward me directly in front of Hartford’s City Hall a few months ago following a public hearing.

Removing flags from an environment erases, temporarily, some of our tl;dr culture. It forces long form. It requires conversation, listening, real attempts at understanding. It snaps people out of thinking and speaking in tweets or sound bites.

Dropping cheap symbolism — that includes but is not limited to national flags — means having to step it up and learn how to articulate our complex feelings and thoughts. I know people who have said they don’t feel right addressing the antisemitism present following October 7th because they see that like centering themselves at a time when the focus should be on stopping a genocide.

There are seasoned voices in the mix, though not nearly enough, who seem influenced by the core of improv: yes, and. Yes, we have to stop the aggression against civilians, and we have to acknowledge that there are people calling for a ceasefire who have said absolutely antisemitic remarks; here, I don’t mean the ambiguous “river to the sea” statement that bends depending on context and speaker, but actual, no-doubt-about-it antisemitism that I need not repeat.

There are other voices able to hold many truths and say this: “we have to be very careful not to dismiss or discredit an entire movement because of its worst elements.”

I understand, on some level, why some people might lean into oversimplified belief systems and symbols. They have more company in those spaces. They might feel less lonely not having to stand alone, which happens often when one rejects what they know is incorrect. At the end of the day, how comfortable are they feeling with their choices? I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to equate flags with gang colors. The mentality of wanting to belong is about the same. People will turn a blind eye to remain part of a group. People are terrified of being shunned.

The secret is that there are others out there who defy this lazy categorization. You just have to look for the others, or, as the organizers of last week’s vigil did, let some folks know that they were hoping to connect, and then stand on the Yale campus holding a sign that simply read “Humanity Vigil.”

The signs distributed to those who wanted them were often in multiple languages, not calling for dominance but collective liberation. They acknowledged the shared humanity.

The group formed a circle, looking at one another, and then began to address one another. There was no yelling at anyone. Without amplification, people spoke about why they were there and what they had been feeling since October 7th (or before). There wasn’t the slick dispensing of slogans or anything showy. There was sincerity, an understanding of what was at stake, and moral clarity. The organizers made it clear in advance and several times at the event that this vigil was not in opposition to the nearby gathering replete with flags — this was a different approach, and anyway, this had been planned a week before pro-Palestinian students began gathering at this new location, having been removed from Beinecke Plaza. Some who had been at that other rally tucked their flags in their bags and came over to join.

When someone new entered the circle, I often could not make guesses as to what their background or beliefs might be. I had to stop to pay attention. I had to listen and make an attempt to understand.

This approach erodes gang mentality. It encourages nuance.

The Humanity Vigil was happening right by a pro-Palestinian protest which got loud at times, but for the most part could have been mistaken at a distance for college kids sunning themselves on the quad. When I arrived before the vigil, I walked around and observed a few people quietly and studiously making chalk art. Someone was playing an acoustic guitar and singing. There was a table of food. I saw artwork reading “books not bombs” and was disappointed to see this was a political statement and not a sign for a table of free books. A bit later a speaker arrived and there was about half an hour of noisiness coming from the quad. Then, it quieted down again. This particular space at this particular time did not feel off in its vibes. It wasn’t threatening on a personal level, though perhaps the administration viewed it as a different kind of threat: this is the time of year for campus tours, and several were walking through the area while students were chanting. College administrations aren’t thinking so much, though, about how the way they manage student speech and expression may impact a prospective student’s decision. Had I a child ready to enter college, I would be steering them away from institutions that send in police who assault young people.

Different tactics lead to different outcomes. Whether they know or would ever admit to it, this generation is modeling sit-ins off of the Baby Boomers anti-Vietnam actions. There’s room for discussion about if any of that proved impactful, historically. As I see it, these college actions may get universities to disclose their investments. Students are consumers and have a right to ask where the money goes. Will students be successful in reaching the goal of divestment? Maybe? Maybe, if they understand their role as consumer and having the right to spend their money (or parents’ money or borrowed money) elsewhere.

Will this lead to the kind of future we want?

That’s where actions like the Humanity Vigil come into play. We have to know how to talk to one another and how to listen. How do we expect world “leaders” to have mature negotiations with one another when our own current atmosphere is not encouraging it? Just as when trying to tackle climate change, a whole range of actions are needed, so they are here, but not every action has the same result and we have to think holistically about the futures we want.

Related Posts

Safe Streets Connecticut: June 2024

Quiet.

Boxing Day Special: Getting Rid of Useless Arguments