Had we chosen to live differently with water, it’s unlikely Hartford would have been so carved up by highways. At least, not ones so bloated

We could have restricted industry from dumping waste in the Park River.

We could have cut our losses and moved out of flood zones, allowing for open space and parks; a temporarily closed walking path and playground is a different creature than flooded residences.

We could have made many different choices, but then, we would not be able to regard the twentieth century as a time when each mistake seemed worse than the one before.

I’ve written about this before, but in short, the push to bury the Park River was not linear, nor was it strictly a way to prevent flooding. The appetite for digging up and then shunting the river into a conduit came from highway and real estate development, and from a distaste for its stagnant and stank aesthetic. Easier to build roads and erect house-after-house when there’s flatter, straighter, more predictable space to work with, and easier to sell people on those houses being built outside the city center when they’re promised easy access via high speed roads. It was cost and fear of additional flooding that delayed river interment as long as it was.

And then, following the notable floods (see signs below), there was suddenly federal money available to prevent flooding.

Early naming really gives it away: Park River Highway and Dike Highway.

Had we done something different than construct a massive north-south dike, I-91 would possibly have been built another way, perhaps with a smaller footprint.

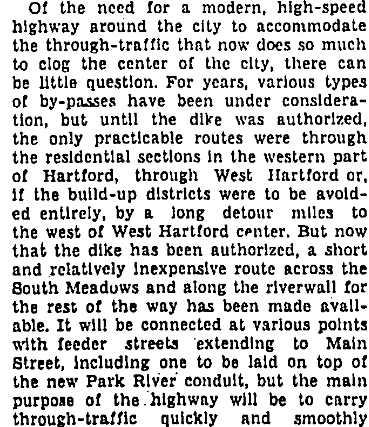

It’s spelled out as such in a 1939 Courant piece:

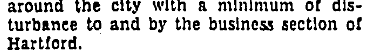

And before that in December of 1936, with the flood commission being the ones to discuss future I-91:

There’s so much documentation of this out there, and someday I will more adequately compile it, but I am always surprised that I continue to hear it said that the Park River “had to” be buried because of flooding. It’s spoken as if this is fact, without much examination. Even though we know that what happened in 1936 was that the Connecticut River caused the issue — not the Park River. Even though there are many newspaper articles, along with various city plans, documenting the thirst for development above all else.

In some of these accounts, it’s not the protection from future floods that gets applauded as the dike is built and the Park River buried. It’s how much more land Hartford gains for “development.”

The Park River has managed to capture the imagination of many locals, but it’s hardly the only body of water in the area that has been desecrated. Cemetery Brook, originating on Cedar Mountain, was mostly driven underground. In this case, people built ridiculously close to it, and somewhere is a photograph of a garage or shed that a person built over the top of it. How do you build a structure over a stream and then be mad about the stream?! The land gained was mostly extensions to people’s lawns. This brook empties into Park River’s South Branch, at a point where everything is so ravaged by humans. A pipe emptying into a concrete basin.

On the other side of the city, we see this with Gully Brook — though that’s less dramatic. You can peek at it from a point in Keney Park, and then it is covered. Somewhere underground it merges with whatever the Park River has been made into, also below the surface. Pipes. Conduits. Containers. It’s not as if they created a shell over the top of flowing water.

We commonly hear about how I-91 interferes with residents’ access to the Connecticut River, and not to let the highway off the hook, but in case anyone hasn’t noticed, there is a whole dike system and that little nuisance of Constitution Plaza — which for the new kids on the block, did not always connect to Riverfront Plaza . . . because that whole addition came later. During the planning phase, there was criticism of the plaza’s height, how it was all one level, how the storefronts were too large and inflexible. People questioned who would want to shop here.

If you’re wondering the link here — I don’t assume everyone reading this has lived in Hartford since 1950 — it’s partially that those living in the tenements along Park River in downtown were, well, living in tenements. The housing probably did need improvement, but there was not much pushback when it came to tearing down the housing of lower income people here, the rest of the Front Street neighborhood, and other locations on the “East Side.”

A “Slum Survey Report” published in 1934 says that the demolition of housing along the Park River in downtown would “make possible the widening of Sheldon Street, the beautification of the river banks as a park and the rehousing of a homogenous group of families of Polish and Lithuanian descent.”

Knock down people’s homes and move them around. I don’t know what site was ultimately decided on for their replacement public housing, but there were a few locations named, and done the way it had been for so long: create areas of concentrated poverty instead of mixing people of different income levels and backgrounds.

They kicked people out of Front Street and instead of building healthier housing, they put up a strange raised plaza. It was the era of “let’s make a network of skywalks so pedestrians aren’t slowing down the cars,” and of course, they figured out later that you kinda need storefronts to be very accessible to people on foot. Cars don’t buy brassieres and fancy hats; people do.

This is why big projects need feedback from a range of people: long time residents who can claim their families were among the first colonizers, and those who have been here five minutes; those who run businesses and those who could care less about economics; those who have a personal vehicle for each member of the family and those who want nothing to do with expensive transportation. You need people in the room who will challenge ideas. Was the river ever something that needed to be controlled, or was it us who needed to practice self-control regarding where we would build homes, factories, and roads? Did it have to be a wall, or could we have worked with something less imposing? If you’re the person in the room asking necessary questions, be prepared for the Very Important People to condescend and talk down, try to make you feel small, belittle your experience. Prepare to keep asking those questions anyway. Without this input, your city gets stamped with half-baked visions manufactured by those with limited interests. Actually, it’s more tattoo than stamp, and while the mark can be removed, it takes a whole hell of a lot of time, expense, and there will be discomfort.

It seems that current mayoral hopefuls are riding some wild “Hartford is not for sale” bit, but for most of the last century, Hartford very much was being sold off to those interested in making money. Each of these candidates should show their resumes for how they have been undoing those crimes, how they’ve been making Hartford a more livable city for residents — current and future. Are they asking tough questions and making things happen, or what? Where have they been and what have they been doing before deciding they could run a city?

Climate Possibilities is a new series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

On The Level

Had we chosen to live differently with water, it’s unlikely Hartford would have been so carved up by highways. At least, not ones so bloated

We could have restricted industry from dumping waste in the Park River.

We could have cut our losses and moved out of flood zones, allowing for open space and parks; a temporarily closed walking path and playground is a different creature than flooded residences.

We could have made many different choices, but then, we would not be able to regard the twentieth century as a time when each mistake seemed worse than the one before.

I’ve written about this before, but in short, the push to bury the Park River was not linear, nor was it strictly a way to prevent flooding. The appetite for digging up and then shunting the river into a conduit came from highway and real estate development, and from a distaste for its stagnant and stank aesthetic. Easier to build roads and erect house-after-house when there’s flatter, straighter, more predictable space to work with, and easier to sell people on those houses being built outside the city center when they’re promised easy access via high speed roads. It was cost and fear of additional flooding that delayed river interment as long as it was.

And then, following the notable floods (see signs below), there was suddenly federal money available to prevent flooding.

Early naming really gives it away: Park River Highway and Dike Highway.

Had we done something different than construct a massive north-south dike, I-91 would possibly have been built another way, perhaps with a smaller footprint.

It’s spelled out as such in a 1939 Courant piece:

And before that in December of 1936, with the flood commission being the ones to discuss future I-91:

There’s so much documentation of this out there, and someday I will more adequately compile it, but I am always surprised that I continue to hear it said that the Park River “had to” be buried because of flooding. It’s spoken as if this is fact, without much examination. Even though we know that what happened in 1936 was that the Connecticut River caused the issue — not the Park River. Even though there are many newspaper articles, along with various city plans, documenting the thirst for development above all else.

In some of these accounts, it’s not the protection from future floods that gets applauded as the dike is built and the Park River buried. It’s how much more land Hartford gains for “development.”

The Park River has managed to capture the imagination of many locals, but it’s hardly the only body of water in the area that has been desecrated. Cemetery Brook, originating on Cedar Mountain, was mostly driven underground. In this case, people built ridiculously close to it, and somewhere is a photograph of a garage or shed that a person built over the top of it. How do you build a structure over a stream and then be mad about the stream?! The land gained was mostly extensions to people’s lawns. This brook empties into Park River’s South Branch, at a point where everything is so ravaged by humans. A pipe emptying into a concrete basin.

On the other side of the city, we see this with Gully Brook — though that’s less dramatic. You can peek at it from a point in Keney Park, and then it is covered. Somewhere underground it merges with whatever the Park River has been made into, also below the surface. Pipes. Conduits. Containers. It’s not as if they created a shell over the top of flowing water.

We commonly hear about how I-91 interferes with residents’ access to the Connecticut River, and not to let the highway off the hook, but in case anyone hasn’t noticed, there is a whole dike system and that little nuisance of Constitution Plaza — which for the new kids on the block, did not always connect to Riverfront Plaza . . . because that whole addition came later. During the planning phase, there was criticism of the plaza’s height, how it was all one level, how the storefronts were too large and inflexible. People questioned who would want to shop here.

If you’re wondering the link here — I don’t assume everyone reading this has lived in Hartford since 1950 — it’s partially that those living in the tenements along Park River in downtown were, well, living in tenements. The housing probably did need improvement, but there was not much pushback when it came to tearing down the housing of lower income people here, the rest of the Front Street neighborhood, and other locations on the “East Side.”

A “Slum Survey Report” published in 1934 says that the demolition of housing along the Park River in downtown would “make possible the widening of Sheldon Street, the beautification of the river banks as a park and the rehousing of a homogenous group of families of Polish and Lithuanian descent.”

Knock down people’s homes and move them around. I don’t know what site was ultimately decided on for their replacement public housing, but there were a few locations named, and done the way it had been for so long: create areas of concentrated poverty instead of mixing people of different income levels and backgrounds.

They kicked people out of Front Street and instead of building healthier housing, they put up a strange raised plaza. It was the era of “let’s make a network of skywalks so pedestrians aren’t slowing down the cars,” and of course, they figured out later that you kinda need storefronts to be very accessible to people on foot. Cars don’t buy brassieres and fancy hats; people do.

This is why big projects need feedback from a range of people: long time residents who can claim their families were among the first colonizers, and those who have been here five minutes; those who run businesses and those who could care less about economics; those who have a personal vehicle for each member of the family and those who want nothing to do with expensive transportation. You need people in the room who will challenge ideas. Was the river ever something that needed to be controlled, or was it us who needed to practice self-control regarding where we would build homes, factories, and roads? Did it have to be a wall, or could we have worked with something less imposing? If you’re the person in the room asking necessary questions, be prepared for the Very Important People to condescend and talk down, try to make you feel small, belittle your experience. Prepare to keep asking those questions anyway. Without this input, your city gets stamped with half-baked visions manufactured by those with limited interests. Actually, it’s more tattoo than stamp, and while the mark can be removed, it takes a whole hell of a lot of time, expense, and there will be discomfort.

It seems that current mayoral hopefuls are riding some wild “Hartford is not for sale” bit, but for most of the last century, Hartford very much was being sold off to those interested in making money. Each of these candidates should show their resumes for how they have been undoing those crimes, how they’ve been making Hartford a more livable city for residents — current and future. Are they asking tough questions and making things happen, or what? Where have they been and what have they been doing before deciding they could run a city?

Climate Possibilities is a new series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

Related Posts

Beyond Hartford: Branford

Hooker Day Parade 2010

Rush Hour Civil Disobedience Draws Attention to Racism