Several decades ago, all adolescents (nobody was a “tween” at this time) were herded into the school cafeteria for an assembly so corny that the message stuck and it takes nothing more than seeing the word “recycle” to hear Ray Cycle‘s song: “Re-re-re-re-re-recycle, Re-re-re-re-re-reuse it. Don’t, don’t, do not trash it. [something something] Don’t abuse it.”

It seemed random at the time. I don’t recall there being a unit on waste management in middle school. Now, I have an educated guess as to what this was all about. There had just been a major Earth Day anniversary, and people were paying fresh attention to the issues they had not quite worked out since the inaugural occasion in 1970. Curbside recycling collection had recently begun in this semi-rural town. Before then, residents would schlep their cans, bottles, and newspapers to a collection point. But in this “Save the Rainforest” era, the small, square blue bins were picked up weekly. Newspapers needed to be bundled and tied. Cans and glass containers needed to be rinsed.

This was also around the time that the town dump closed. Going forward, waste would be hauled out. To where? Away. I don’t recall any discussions of this, about whose communities would wind up with our junk. Now, I have a better idea.

Curious to see what my ex-town has been doing since, I learned that they have, some time in the last thirty years, moved from blue bins to barrels on wheels. Although they also have a single-stream system now, it is interesting that the small town residents are given more specific advice than what is told to Hartford’s residents: rinse food particles from containers, do not flatten cans, and by the way, don’t even think of dropping anything that’s been in contact with motor oil or pesticides in that bin! These municipalities use different facilities, but is the process so varied that Hartford residents are not provided detailed instructions?

There is very little that the state capitol has in common with this former farm community, but there is one thing: deer carcasses. Hartford’s recycling center has encountered these in recent years, and in the first week curbside recycling occurred in my hometown, back in 1990, there was an attempt to recycle a dead deer by placing it in a trash barrel. It’s hard to know who to judge more harshly: those with ample outdoor space in which a carcass can be buried, or those still attempting this thirty years after recycling became mandated statewide.

About three years into this experiment, the hometown switched to biweekly (that’s every other week) curbside recycling collection, yet maintained weekly garbage collection. Then they returned to weekly collection. Then, about five years ago, they went back to biweekly. With this move, my ex-town issued residents even larger rolling bins. That was the default. If someone felt the smaller (yet still large) bins were enough, it was on them to contact the town and request no new barrel be dropped off.

That’s part of the problem.

When we look at what’s going on in Hartford, we have to scan the entire landscape to see what clues are out there about why people are still terrible at what was an easy lesson to grasp for those of us lucky enough to be forced to chant “Re-re-re-re-re-recycle” while doing the Arsenio Hall-style, fist pump in a lunch room.

Hartford’s version of the biweekly recycling collection is this: trash cans larger than recycling cans.

Both practices set a clear expectation: you are going to create more landfill/incinerator waste than the kind that can be recycled.

What is Hartford’s situation?

Some of us already knew our recycling program was in trouble, but last month the news gave us a clear picture as to how troubled. According to WNPR, ” Over the last two years, the amount of material sent for recycling in Hartford has dropped by about 75%.” This does not mean people are wheeling blue bins to the curb 75% less; it means most trucks are rerouted to the incinerator.

Why? Contamination.

After three decades, people still are not separating trash from recycling properly. Some kindly attribute this to “wishful recycling,” the assumption that anything except the most obvious (food waste, soiled diapers, etc.) items can probably be recycled. There probably was a time when a take-away coffee cup, for example, could have been recycled. It’s cardboard, right? But these are usually lined with plastic. No longer recyclable.

Combine poor public education with irresponsible corporations producing single-use disposable items, along with a previous initiative that rewarded people not on how correct their recycling was but on how much their bin weighed, plus a smattering of people who just do not care about what happens with their waste so long as it goes away from them, and mix in an absence of immediate consequences. . . and we have this situation.

Another way to think of it is like this: Americans are as terrible at recycling as we are at driving because education is often treated as this one-off. We don’t renew our licenses: we renew our photograph and address information. License renewal would mean routine eye exams, written tests, and road tests, with study materials doled out annually explaining new laws and infrastructure, while reminding motorists of the basics. Unless someone has a suspended and revoked license, no additional education is mandated.

While my middle school recycling education was awesome, there has been nothing quite so formal in the years since. There was not even a follow-up lesson on this in high school. I care about my habitat, so I do seek out information on this subject, but all these years, I could have been dumping my cans into the garbage or committing various recycling sins. . . and receiving no reprimand with education unless making an especially egregious action, like loading the entire bin with motor oil containers or filling it to the brim with weeds.

Right now, because of crisis mode, there is a slightly elevated attempt at education. Would we see this sense of urgency, though, had the incinerator not been on its way out? Imagine how, if there had been respect for the health of those living near the incinerator years ago, we would be having a different conversation today, already having had resolved these basic issues.

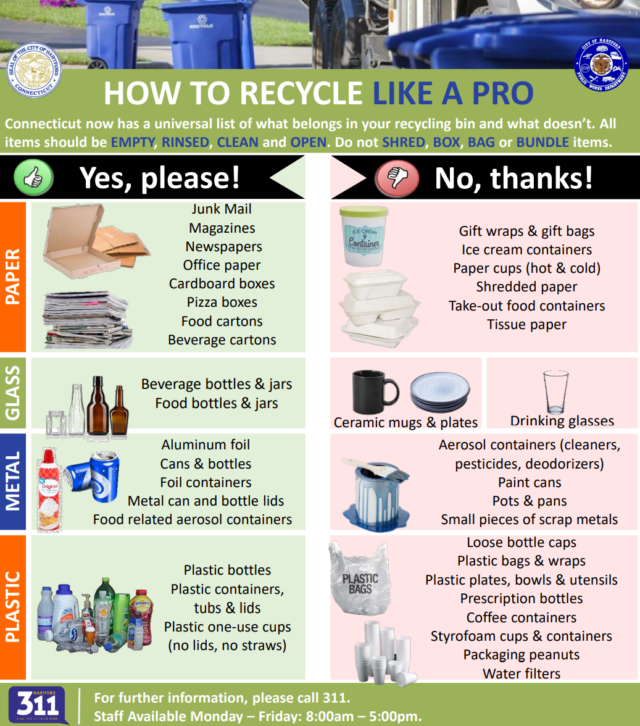

The City of Hartford provides this info, which was just emailed to whomever is on the City’s mailing list:

What do you do with [weird object in your possession] that is not specifically listed? Go to the RecycleCT website and look it up. They tell you if it should be recycled curbside, trashed curbside, or be discarded some other way.

Because this is not 1990, we have the ability to Google “how do I discard my deer carcass.” Thirty years ago, you would have needed to make a landline call to get an answer for that question. There’s really no excuse.

Yet, spend any time in neighborhoods that get socially dumped on, and you’ll see how they get literally dumped on: tires, mattresses, nips, Crazy Cowboy cans. . .. Why am I seeing a growing pile of tires outside of Pope Park North when you can leave tires with those places that sell tires? If someone has managed to purchase and move a mattress into their home to start with, how then does it become so impossible for some to later discard these in ways that do not involve tossing it down an embankment or dragging it to the middle of a vacant lot? The City of Hartford accepts a generous amount of bulky waste before charging a fee, and the only catch is that you schedule a pickup.

Despite all this aggravation, I am seeing more aggressive attempts by the City of Hartford to correct errors: leaving offending bins uncollected, with an infosheet attached so residents can make corrections. There is promise of fines for repeat offenders, though who knows if that will come to fruition. A hit to the wallet is also a way to educate. Those who teach know that students do not all learn in the same way, and so it is true for adults requiring education about how to manage their waste. A friendly, informational email is enough for some; the annoyance of an uncollected blue bin will work for others; the expense and/or irritation of a fine is what may be needed, still, for others.

And, despite the grumbling that comes with any change, ever, in Connecticut, we need bolder action.

Every week, trash barrels and blue bins overflow. Lids propped open by greasy pizza boxes reveal attempts to recycle anything from food to dirty diapers. Walk by around sunset, and you’ll have rats darting by your feet.

The status quo solution has been to demand more and bigger barrels, unlimited free bulky waste pickups. But it’s precisely that way of thinking that got us here. Widening highways never cures congestion. Oh, it may for a moment, but then we experience induced demand: without a robust public transit system, without incentive to carpool, without sincere pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, that highway is going to get clogged again. Providing more trash barrels enables a trash problem, especially when up until now, the City has done little to encourage any behavioral changes.

Start by encouraging reduction of waste, period. Most people alive today have been socialized to believe that disposable culture is the essence of our American identity, but it was not always that way. Reducing single-use items, in particular is one way to cut waste. For instance, it’s not that hard to tell people to bring their own water bottle to an event, which they can refill there, rather than providing plastic-wrapped water for them. Even better would be public education about the water quality in Hartford. Why is anyone buying water when clean, safe water is coming out of our taps?

Instead of only focusing on what we do with stuff when it’s “done,” we need to honestly assess what we’re purchasing/obtaining/allowing to enter our lives, and why. This conversation was largely absent over the last forty years, though, as one can see in any look at the implementation of recycling programs. They talked about how to get people to dispose of materials in one way, and even how to get them to consume materials made from recycled goods, but not how to reduce their consumption in the first place. In all the locally-produced newspaper articles I have read on recycling, I only found this suggestion emerge once, and it was in a wildly sexist piece in 1971, essentially sticking “housewives” with the burden of this task; their concept of waste reduction, by the way, was to install a trash compactor in kitchens — so, buying a gadget that does not reduce waste at all.

Educate about composting organic materials and provide an affordable way for more residents to do this. An indoor worm bin is great for small households who aren’t in a cramped living space, but I know that not everyone wants worms as pets (though they should!). The people who, every single week, are not breaking down their cardboard so the recycling bin’s lid can close are likely not inclined to cut cardboard and food scraps into one-inch segments to appease the basement worm farm.

So, the municipality can make it easy to get the desired behavior (creating less waste, composting organics, sorting properly) and difficult for the collective self-harm to continue.

What has worked in some places has been for municipalities to weigh residents’ trash cans each collection day and share that information with them. Many individuals who have sought to waste less began with a trash audit — gathering all of their trash for one week. . . so, not leaving waste in cans at work or on the sidewalk. When you have a realistic sense of how much you use, there are few among us who would not be appalled.

Collect trash bins less frequently. Adopt a variable-rate pricing policy, which is absolutely an equity measure. According to the EPA, the average American produces 4.9 pounds of trash per day. If my daily contribution to the trash and recycling is under one pound, why should my taxes subsidize the wastefulness of someone down the street who can’t/won’t figure out how to do better?

We already pay for our water. It costs very little if we use it responsibly. Those who are overwatering their lawns or ignoring plumbing problems are the folks who have expensive bills. We pay for our electricity. We pay for our gas. Why not this? Nobody need to panic — other towns in Connecticut, and elsewhere, are already doing this.

Most importantly, research and adopt what other places — including those outside Connecticut — have done. We do not need to be that creative to fix this, and it absolutely is fixable!

Dispatching DPW crews constantly to deal with illegal dumping should not be the norm in Hartford. Neither should burning most of our recycling. What’s increasingly clear is that a variety of tactics are required to fix the problem, including much more robust public education and solid communication between City and residents for both any new programs and our existing procedures. If we work from the assumption that the majority of Hartford residents are bright, caring people with the capacity to learn new information and adopt new behaviors, it is possible for us to stop seeing shameful articles about how we can’t handle our own waste.

Eric Dobbs

As a 90s child who had the same kinds of assemblies and “special guests” in class about recycling, I remember very distinctly they talked a lot about the three Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle.

And now some thirty odd years later, it seems like the only one anyone is still talking about or doing in daily practice is “recycle”.

Recycling can only do so much of the heavy lifting, especially with plastics. And there’s just SO MANY issues now with plastics, be it how it’s harder and less lucrative to recycle some, and how much we have so much more single use plastic.