Ahhh, the good ol’ days. When a typical Saturday morning in the city meant listening to the civil defense sirens blaring (or not) in Hartford.

On very special days — like Flag Day of 1954, when President Eisenhower signed into law the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance — a mock attack required active role playing from the general population for seventeen minutes.

The scenario was printed in the paper: The United States would learn that 425 “Soviet” planes were coming to attack the states, its territories, and if that were not already quite the scenario, they threw in a few Canadian cities for an extra dose of terror. “Approximately 125 of the planes will be blasted out of the sky but the remaining 300 will get through to their targets. Most cities will get a warning of from 54 minutes to two hours” Sirens would be activated simultaneously throughout New England, New York, and New Jersey, and 42 cities across the nation would be “bombed.” Hartford would be the only target in Connecticut, with an atomic bomb 2.5 times more powerful than that dropped on Hiroshima, detonated above Main and Church Streets.

The expectation was for people to flee from cities to the suburbs. Stations were set up at parks on the edge of Hartford to help. Yet, there was a mixed message that those in the middle of the action should seek shelter. During the drill, traffic would be stopped and those on foot would be sent to shelters.

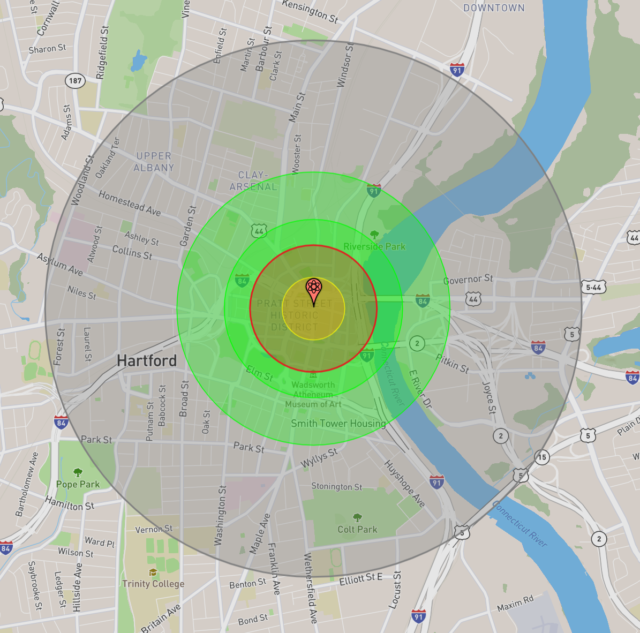

It’s alternately enraging and hilarious. Enraging that instead of top officials learning how to resolve conflicts like adults interested in the progress of humankind, they put regular folks at risk, expecting us to both play along and foot the bill. Hilarious, because one look at a NukeMap shows how much time was wasted with certain aspects of these drills. The image below uses the specs provided in that scenario from June 14, 1954. Click through to the original page for all of the details, but everything in bright green would have been immediately and significantly impacted.

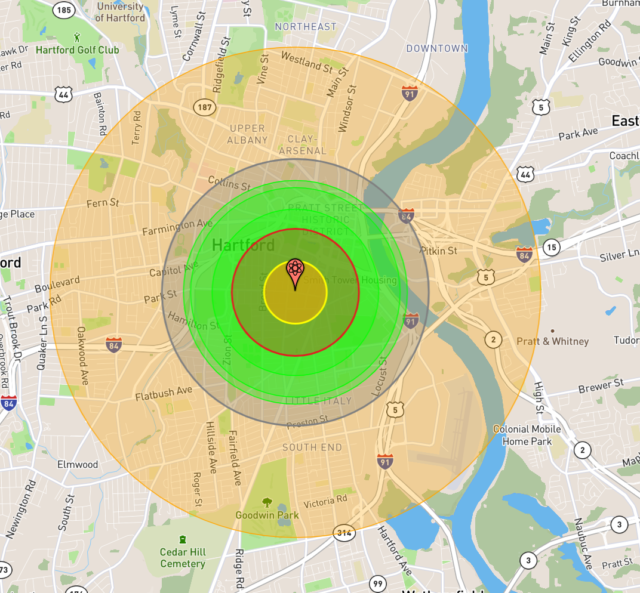

That drill almost 70 years ago was not the first or last one Hartford experienced. One year someone got more imaginative and devised a scenario of a 100 kiloton bomb detonating at ground level by the intersection of Park and Cedar, not far from Hartford Hospital and the State Capitol. Here’s what that would have looked like:

If you go into the app, you can apply other settings to get the full range of impact. The image above is set to only show the most severe, short-term ones; nobody should read this to mean that most of Cedar Hill Cemetery would have been a safe zone

One time, instead of making Hartford the center of suffering, we actually had the chance to send assistance down to Norwalk, days before Christmas when shoppers had clogged the streets. “Operation Snowball” revealed something interesting: of the 22 communities asked to participate, ten declined. Seems like people had things they wanted to do besides think about death and destruction during the holiday season.

An emergency drill in 1943 resulted in confusion because sirens from other parts of the city could be heard in downtown before those in the central business district were activated. People thought they were getting an all-clear signal and began to leave shelters, when they were ushered back by police.

Numerous other “civil defense” drills over the years showed the same issues: sirens delayed or not working at all. Small towns experienced 10-15 minute delays. Some places were never reached by the sirens; they were not loud enough to be heard inside larger office buildings, and that was just in Hartford, where there were 33 sirens at the time. A factory section of Frog Hollow was one area where sirens were faint.

It was not a perfect system. A siren in Windsor Locks was silenced by a bird nest. Blizzards knocked sirens out. One in New Britain caught fire during a test. Hartford’s fire chief was noted as saying “you can’t expect to hear the siren inside your house with the radio, TV, or the washing machine going.”

The more errors that materialized during one of these events, the more likely it was that a Civil Defense official would be quoted declaring the practice a success.

These mock events seem to have been more about ritual and a feeling of preparedness than actual life-saving skills, at least for those most likely to be in targeted areas. During WWII, blackout defense drills had people turning off all their lights, as if they were warding off trick-or-treaters, not enemy combatants. Opinions vary on how effective blackouts were when it came to deterring aerial attacks, but as far as the practice runs around here went, those who did not go with the flow were named in the paper and/or fined and/or arrested.

The activity of wandering in the dark has its own set of hazards, but the drills were complicated for other reasons. One “lights out” event, taking place after 9 PM, resulted in 100 people hanging out at the Isle of Safety because nobody knew which nearby shelters were open and it seemed like a toss up between staying on the buses or using something that had “safety” right in its name. As it turned out, 15 Asylum Street was an official shelter and open, and several other locations were identified on Pearl Street. Were no air raid wardens were available or armed with that information?

It’s good to iron out potential problems with such scenarios, but the Cold War exercises brought into question if those designing the protocols even bought into them.

During one of the mock attacks of the 1950s, downtown banks were praised for locking up valuables before the employees sought shelter. At other times, banks were ordered closed ahead of the drills.

The newspapers published instructions for what folks should do when the sirens sounded. Those driving were advised to pull over, exit, and run to safety. Motorists were told to stay away from bridges and to not park on certain ones. If on a bus, it would pull over, passengers would be issued transfer tickets, and they could opt to find shelter or stay on the bus. For more realism, why not suspend fare collection for the day? In a true emergency, no driver is going to ask for a ticket — not even the cranky guy who used to run the 56 route. Truck drivers were told that those “with valuable cargo may remain with their parked vehicles.” At the same time, people were specifically told to not enter private homes. Is this what it looks like when every day is full of fear, but also there is a strange focus on protecting property?

It’s easy to mock these drills, but it’s not like we have evolved spectacularly in the years since. Look at the active shooter drills of today. It took two decades before they began receiving the criticism they deserved from the start: they are psychologically damaging without providing enhanced safety for students, and there have been real violent incidents where people assumed they were merely experiencing a drill.

Civilians did not always take nuclear preparedness as seriously as some would have preferred and plenty questioned the practice early on.

A former war correspondent published his observations in 1955 of a recent drill in Washington DC: “while government evacuation was being practiced on a grand scale, sidewalk salesmen continued their spiels and many shoppers hardly moved their noses from display windows.”

By 1956, people locally began to show signs of high alert fatigue. The town of Manchester struggled to get volunteers involved. When a fire broke out at an autobody shop in Torrington in 1957, off-duty and volunteer firefighters ignored the alarm, assuming it was yet another test of the civil defense (CD) system. By word-of-mouth they were notified and able to respond, but the shortage of help likely contributed to excess damage. Then, in Harwinton, there was disappointment that not one person showed up at CD headquarters during an alert to receive emergency response training. When New Britain decided to upgrade its sirens, they removed the old ones before the replacements were ready to install; the town experienced silence during a scheduled test. Persistent apathy was criticized, mostly by those running civil defense operations. Instead of looking at how the United States could keep itself out of violent spats, they wanted the people to buy into amazingly off-kilter uses of economic and natural resources, like systems of air conditioned underground highways that would serve as massive bunkers. Yes, that idea was floated out there by some proponents of civil defense.

By the end of the decade, apathy, for some, transformed into active opposition. During a mock attack, close to 20 people were arrested in New York City for holding anti-war signs and refusing to shelter indoors. Middletown police would arrest two people in 1961 for disobeying officers’ orders to go indoors. In New Jersey, people outside of bomb shelter/bunker exercises protested military spending.

That year, there were practical questions about the effectiveness of emergency plans. Overuse of sirens was blamed for making people complacent, which could cause trouble in a true emergency. Others decided that instead of sheltering-in-place, children should rapidly return home as soon as it was safe to do so. There was a new focus on not splitting up families, and the focus shifted from communal to household fallout shelters, burdening civilians with protecting their families from the fallout of conflicts they typically had no part of. To this day, signs remain to tell of where some of these shelters are/were.

What to do about families was but one question. A long piece of criticism published in the New York Times (1963) talked of how evacuation plans had been dropped: “The hope for flight to safety by means of motor transportation has been overwhelmed by the number of vehicles themselves. . . [Los Angeles’] great network of freeways, it is believed, would probably prove to be a death trap.” (Fast forward to 2018 when a highway proved to be just that for those fleeing wildfires) Sure, we evacuate the shoreline when hurricanes approach, but those offer a more predictable threat and even when a town is trashed by weather, people can more readily return home to a battered beach than to a place with nuclear contamination. Thus, there were questions as to how prepared suburban and rural areas would be when it came to accepting large numbers leaving a place permanently, either while under attack or in anticipation of their home being a target.

That article claimed “reports gathered in a score of cities across the country make it clear that except in a few instances, civil defense organizations range in competence from inadequate to hopeless.” The writer shared that Oregon had just ended its involvement in the CD program, to which Hartford’s fire chief responded that it was a “ridiculous” decision; Hartford, meanwhile, was expanding its own program, of which the federal government footed only half the bill. Shortly after, Wethersfield’s town manager pushed for its City Council to drop participation in what he called a “sham program” that was outdated and expensive. Wethersfield had to rent and maintain the sirens, he said, and it felt silly to direct people to shelters they had no intention of creating. It took over five years, but the council eventually voted unanimously to stop participating.

Other places allowed sirens for non-emergency purposes. Manchester decided to sound them to kick off a fundraiser. New Britain discussed using them to announce parking bans. Meanwhile, residents in Newington petitioned to remove a siren because it doubled as a fire alarm and the sound was keeping people up at night.

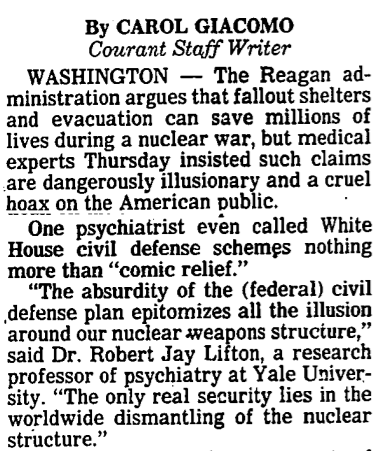

Throughout the 1970s, though, siren tests continued elsewhere, dwindling in frequency. They all but stopped in the 80s, though not without President Reagan’s administration first trying to renew a case for all the trappings of the Cold War:

Long after other towns abandoned the siren tests, Windsor Locks continued with annual ones in 1999 and sporadically after until at least as recently as 2007. Vernon also tested its equipment in 2007.

There is no reason to preserve the yellow sirens, aside from enjoying roadside reminders of weird history. Despite the bravado shown as they failed over and over again, their shortcomings were understood at the time, evidenced by attempts to find functional indoor warning systems. In the 1950s the government was dreaming of and designing buzzers for inside each home. These NEAR (National Emergency Alarm Repeater) systems would be plugged into electrical outlets, which relies on the power working. Presumably, people would be able to hear them even while doing laundry. The Kennedy administration renewed buzz of this coming attraction in 1961 with an announcement that they were on the way, and in 1962 the Office of Civil Defense patented them. You can guess what happened next. Deep funding cuts put this on hold, though no official reason was provided for the eternal pause.

There had been an earlier indoor system — CONELRAD — which was susceptible to false alarms. This was replaced in 1963 with the Emergency Broadcast System, which included weather warnings; more recently (okay, in the 90s) that was upgraded to the Emergency Alert System, with EAS broadening the type of alerts and how they could be delivered. Besides not needing to be tethered to a device that relies on electricity to work at all, we can get messages in writing and have the phone flash lights at us or vibrate– useful for those who cannot hear anything, and whose needs seemed to be forgotten during that other time.

The reality is that we are kind of awful at emergencies. We almost immediately knew something nasty was brewing at the tail end of 2019, but months later when it reached the United States, we grappled with shortage of medical supplies and hospital beds. When a disaster’s warning time is reduced from weeks to days to minutes, why would we expect to fare better?

Too long; didn’t read: First of all, how dare you. Secondly, I am grateful to have grown up in the sweet era when we had neither Cold War nor active shooter drills. Just non-terrifying, occasional fire drills (weather-permitting) that were to-the-point and proved not one of us was willing to be a hero to save a school building on fire.

Richard

I remember while growing up and the air raid siren blew we were all suppose to go into the basement and hide under the steps. If at school we got under our desks. At home my grandmother refused to go into the basement telling us, if they drop the bomb we will all be dead even if we are in the basement. In my neighborhood we had Sunday afternoon sing a long’s. (what a simple time) Bessie would open the French doors to her house and sit there playing the organ, a older friend Peter knew many of the days folk songs and we all sang. Even the church ladies came and Bessie played hymn requests. It was at one of these that Anne spoke about sitting outside in Union Square protesting the civil defense BS (she had been on the ban the bomb march) along with folks from the Catholic Worker and the War Resisters League. It was at these sing a longs that a small civil rights and peace movement began in a small New England town. After hearing about the sit out some of us never went into the basement again. Yes many of us knew at that time that the world had to dismantle weapons of war and that there was no safety under the basement stairs or under a desk. Though we lived some 20 miles from Hartford we always thought that the bomb would drop on Pratt and Whitney in East Hartford because of the war industry there. As far as evacuation goes, I will be staying right in my home even if a bomb is dropped on Pratt only 1.5 miles away. Ha ha on all the cars trying to escape, my goodness look at rush hour now and that is just going home.

Thanks for this very interesting article. Great job.