Some places don’t want to be found.

That was my experience with Fort Shantok, a site in New London County that took me three attempts to locate.

Technology thwarted my first attempt. Within a mile of Fort Shantok, my GPS was seemingly blocked. Then the car radio also fizzled. When the vehicle tailing me turned off the road, both systems returned, but I took this as a sign to move along.

On my next attempt, I looked for physical signs, but saw nothing obvious pointing me in the right direction, and I was still weirded out by the previous experience.

On my third attempt I just pulled into the area where I suspected the park was and took a look around. You can’t miss all the highway signs pointing toward the casinos, but Fort Shantok does not announce itself, at least not to someone trying to safely drive and navigate simultaneously.

One entrance to the park reveals what looks to be a basic, town playground. The other: a burial ground, fire ceremony site, and Freedom Forest at Shantok, Village of Uncas. There are views of the Thames River and steep stairs to a picnic area beside Shantok Brook, though that area can also be accessed more directly from the parking lot level.

I don’t recall learning anything in school about Mohegan history, even though that would have fallen during the time that the tribe was suing to get its land back. I like to know something about the places I visit, so since I didn’t get taught apparently anything in school¹, I did some research.

One book I encountered was “compiled and arranged” in 1896 by Henry A. Baker. The History of Montville, Connecticut, formerly the North Parish of New London from 1640 to 1896 may be valuable for its genealogical information, but the text that comes before this is list of former residents shameful, yet it got published by Hartford’s Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company.

We know through policy and action, and through the works of fiction, how colonists and their descendants viewed indigenous populations, but seeing it spelled out so clearly in non-fiction is something else entirely.

Baker wrote: “Montville was a savage wilderness, entirely possessed by a race supposed to have been of Asiatic origin, and may have been, as some historic writers think, descendants from some of the ten lost tribes of Israel.”

I should have stopped reading there, but I was curious where this author’s mind was going, and if he was merely daft, or about to veer hard racist.

“There are a few still remaining that bear the tints of that savage and ferocious race that once roamed over this territory of ours, but now how unlike them,” Baker continued. “They have outgrown their native barbarous condition and become refined by contact with civilization.”

Baker wrote: “Had the aborigines of this land remained unmolested […] by Europeans till the present day they would have been as rude, as poor, as warlike, as disdainful of labor, and in every way as uncivilized as when the white man first explored the river Thames and sailed along its virgin shores.”

We know this language is more-or-less used by racists and xenophobes to rally their troops against whoever is seen as the threat du jour, continuing through to today with the gross “immigration invasion” rhetoric, which is so blatantly ironic it’s hardly worth pointing out.

Encountering this book makes one wonder about the accuracy of historical information — the stories we think we know.

Michael Leroy Oberg, author of Uncas: First of the Mohegans, says it better: “Writing the biography of an American Indian leader is fundamentally a difficult task, especially when that leader was born over four hundred years ago. The evidence is ambiguous and, at times, difficult to decipher. Almost all of it is second-hand, in that Unca’s words and deeds come to us translated by English observers who did not always understand the language and culture of their native neighbors. Even with attention to archaeological research and oral tradition, important ethnohistorical sources, one still must rely on evidence that raises all sorts of interpretive challenges: the problems of bias, perception, and incompleteness that historians and ethnohistorians have long confronted in their attempts to reconstruct the early American past.”

As I read newspaper accounts of Shantok, Montville, and the Mohegan tribe, I kept this in mind, noticing how even within one paper — the Courant — there was an evolution in reporting, moving toward actually getting quotes from members of the Mohegan tribe in more recent years.

What follows comes sources that seem more trustworthy than Baker, though the earlier accounts from the Courant I would still consider incomplete.

Oberg wrote that “[t]he story of Uncas begins with the land. Land rested at the heart of all things.”

Oberg wrote, “The largest Mohegan settlement site, at Shantok, built upon a triangular promontory on the west bank of the Thames well before the Mohegans had developed close contact with Europeans, could easily have housed a population of several hundred people.”

I’m not going to give you a full history lesson here, but needless to say, accounts more recent than Baker’s offer different perspectives on what Montville was like pre-contact.

In 1645, the Mohegans were besieged by the Narragansetts on a bluff overlooking the Thames River. The Narragansetts attempted to starve them out, but Mohegan Sachem Uncas reportedly had a hunting buddy — Thomas Leffingwell, an English guy down in the Saybrook Colony, who showed up right on time (after being sent for). Leffingwell and his English crew sent beef, corn, and peas in a canoe to the fort under the cover of darkness. The Mohegans were able to flaunt their food, and show the Narragansetts that they were not nearly on the verge of being conquered. In return, the tribe sold to Leffingwell (et al.) the land that would become known as Norwich.

In 1898 the Monument to Leffingwell (pictured above) was unveiled by Uncas Gray, a descendant of Sachem Uncas. It was erected by the Colonial Dames from Fort Shantok stones and intended to resemble a cairn. It can be seen today within the burial ground at Shantok.

Fast foward to February 1925, when the Courant reported that New London County “will make a strong bid for an appropriation for a state park […]. There are three bills before the session providing for state parks in the county, one in Waterford, one in East Lyme and one in Montville. The latter, appropriating $15,000 for the purchase of the Fort Shantok site is considered as having the best chance.”

The paper does not spell this out, but Fort Shantok is taken by eminent domain in 1926. Later that year, the opening of the Fort Shantok State Park is announced. It spans 120 acres and includes what the Courant calls an “old Indian burial ground.” Thirty acres, described as an historic site, are added to the park in 1930. These are north of the village site. This area becomes a popular spot for striped bass fishing.

With the Cold War underway, United Nuclear opened its plant on Sandy Desert Road in Montville in 1959, south of Trading Cove, north of Fort Shantok State Park — because placing a nuclear facility right near a state park seemed reasonable. The factory made nuclear reactors for submarines.

Anthropologists from Columbia University, a few years later, discover the remains of the actual fort within Fort Shantok State Park. This includes three fortified walls, pits for storing grain, and both animal bones and oyster shells. You might think that this would immediately lead to better treatment of the surrounding environment. Nope.

Nearby high school students, in 1972, like others of the time, had an Ecology Club. It went on a “pollution tour” visiting various sites in the area. One of these was a stop at the Connecticut Light and Power plant on the banks of the Thames River, near Fort Shantok. Here, the students “took water temperature readings which were later fed into a computer at the plant which showed water temperature at the discharge point was 30 degrees higher than at intake,” so reported the Courant.

In April 1974, the State of Connecticut announces plans for an Indian culture museum and the addition of a boat launch at Fort Shantok State Park. Money for the museum had been earmarked as of 1969, but like many plans, it took five years for the State to get around to looking like it might act.

Within one year of that new momentum, however, the Mohegans launch a lawsuit against the State in an attempt to get Fort Shantok back, citing concerns with cemetery desecration. The wooden headstone posts were being burned by fishermen seeking warmth. Adding a boat launch would no doubt make the area more of an attraction.

By 1977, the Mohegans are looking at Fort Shantok, plus land being used by the State police barracks, Montville Correctional Institute, parts of Route 32 and Connecticut Turnpike, and a segment of the Thames River. In 1978, Connecticut claims the Mohegans waited too long to take action. Mohegans, trying to get federal recognition as a tribe, are denied their request in 1989.

In 1990, UNC Naval Products begins layoffs: about 10% of their 1000 employees are cut. By 1992, UNC Naval Products (United Nuclear Corporation) plant is in the process of being decommissioned while fulfilling a few lingering contracts; by then, there are only around 150 employees remaining. About 10% of UNC’s workforce lived in Montville. This is happening at the same time as Electric Boat is doing their layoffs. And for those who have trouble placing Montville, it’s not an easy commute to New Haven, Hartford, Providence, or Springfield.

Meanwhile, around this time, the Mohegan tribe installs Gladys Tantaquidgeon as medicine woman, with the ceremony taking place at Fort Shantok. The following year, the park becomes a National Historical Landmark. The Mohegans again go after 600 acres of State of Connecticut-owned land, including Fort Shantok.

In March 1994, the 968 member tribe receives federal status, making them Connecticut’s second federally recognized tribe after the Mashantucket Pequot. What helps them finally get this status is that they managed their burial grounds over the years, proving continuity.

The tribe’s lawyer comments, as they are still seeking those 600 acres of land, that the only non-negotiable in this is Fort Shantok, where ancestors are buried, and where they held a drumming and dancing celebration of their federal status.

The Montville area has a strong need for employment that is not driven by war. In comes gambling and entertainment. The Mohegan tribe, in May 1994, suggests a casino and theme park be built on the former United Nuclear Corp. site. Mohegan Sun (minus theme park) opens in October 1996.

After much discussion over whether or not the State can transfer land to the Mohegans, or rather, how this can happen (should then Governor Weicker be allowed to veto?), it’s reported that most of the parkland is returned to the tribe in August 1995. Melissa Fawcett, the Mohegan tribal historian, says: “It’s the first time the governor of the state of Connecticut has signed anything to the tribe instead of signing something away from the tribe.”

Yet, even in 1997 and 1998, the Courant is still writing about Shantok as if the sale never happened. Confused? Yep.

The New York Times reported that Fort Shantok was sold back to the Mohegans in 1998, and put into trust with the federal government. They are not, however, given the land. The Mohegans pay $3 million to the State of Connecticut to get the land they began suing for in 1975.

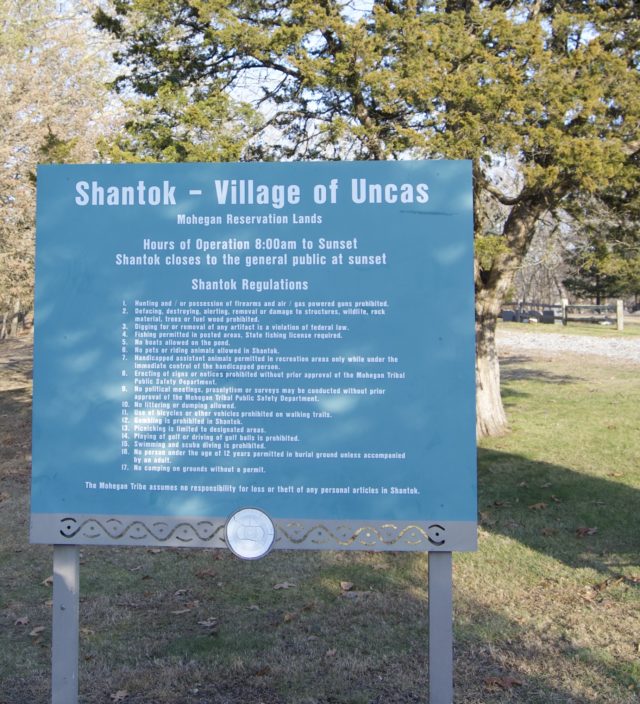

Shantok, Village of Uncas, continues to be a site for ceremonies and festivals today. The rules for use are clearly posted in more than one language. Judging from the absence of litter and ruckus, people are following them.

Fort Shantok Archaeological District — since it does not belong to the State of Connecticut, it’s not Fort Shantok State Park anymore — is located on Massapeag Side Road in Uncasville.

¹Okay, to be fair, in high school there was a Connecticut History class and one of my favorite teachers even taught a Native American history course, but I did not manage to enroll in either because I was a teenager and probably prioritized filling my schedule with study halls.

Shantok, Village of Uncas

Some places don’t want to be found.

That was my experience with Fort Shantok, a site in New London County that took me three attempts to locate.

Technology thwarted my first attempt. Within a mile of Fort Shantok, my GPS was seemingly blocked. Then the car radio also fizzled. When the vehicle tailing me turned off the road, both systems returned, but I took this as a sign to move along.

On my next attempt, I looked for physical signs, but saw nothing obvious pointing me in the right direction, and I was still weirded out by the previous experience.

On my third attempt I just pulled into the area where I suspected the park was and took a look around. You can’t miss all the highway signs pointing toward the casinos, but Fort Shantok does not announce itself, at least not to someone trying to safely drive and navigate simultaneously.

One entrance to the park reveals what looks to be a basic, town playground. The other: a burial ground, fire ceremony site, and Freedom Forest at Shantok, Village of Uncas. There are views of the Thames River and steep stairs to a picnic area beside Shantok Brook, though that area can also be accessed more directly from the parking lot level.

I don’t recall learning anything in school about Mohegan history, even though that would have fallen during the time that the tribe was suing to get its land back. I like to know something about the places I visit, so since I didn’t get taught apparently anything in school¹, I did some research.

One book I encountered was “compiled and arranged” in 1896 by Henry A. Baker. The History of Montville, Connecticut, formerly the North Parish of New London from 1640 to 1896 may be valuable for its genealogical information, but the text that comes before this is list of former residents shameful, yet it got published by Hartford’s Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company.

We know through policy and action, and through the works of fiction, how colonists and their descendants viewed indigenous populations, but seeing it spelled out so clearly in non-fiction is something else entirely.

Baker wrote: “Montville was a savage wilderness, entirely possessed by a race supposed to have been of Asiatic origin, and may have been, as some historic writers think, descendants from some of the ten lost tribes of Israel.”

I should have stopped reading there, but I was curious where this author’s mind was going, and if he was merely daft, or about to veer hard racist.

“There are a few still remaining that bear the tints of that savage and ferocious race that once roamed over this territory of ours, but now how unlike them,” Baker continued. “They have outgrown their native barbarous condition and become refined by contact with civilization.”

Baker wrote: “Had the aborigines of this land remained unmolested […] by Europeans till the present day they would have been as rude, as poor, as warlike, as disdainful of labor, and in every way as uncivilized as when the white man first explored the river Thames and sailed along its virgin shores.”

We know this language is more-or-less used by racists and xenophobes to rally their troops against whoever is seen as the threat du jour, continuing through to today with the gross “immigration invasion” rhetoric, which is so blatantly ironic it’s hardly worth pointing out.

Encountering this book makes one wonder about the accuracy of historical information — the stories we think we know.

Michael Leroy Oberg, author of Uncas: First of the Mohegans, says it better: “Writing the biography of an American Indian leader is fundamentally a difficult task, especially when that leader was born over four hundred years ago. The evidence is ambiguous and, at times, difficult to decipher. Almost all of it is second-hand, in that Unca’s words and deeds come to us translated by English observers who did not always understand the language and culture of their native neighbors. Even with attention to archaeological research and oral tradition, important ethnohistorical sources, one still must rely on evidence that raises all sorts of interpretive challenges: the problems of bias, perception, and incompleteness that historians and ethnohistorians have long confronted in their attempts to reconstruct the early American past.”

As I read newspaper accounts of Shantok, Montville, and the Mohegan tribe, I kept this in mind, noticing how even within one paper — the Courant — there was an evolution in reporting, moving toward actually getting quotes from members of the Mohegan tribe in more recent years.

What follows comes sources that seem more trustworthy than Baker, though the earlier accounts from the Courant I would still consider incomplete.

Oberg wrote that “[t]he story of Uncas begins with the land. Land rested at the heart of all things.”

Oberg wrote, “The largest Mohegan settlement site, at Shantok, built upon a triangular promontory on the west bank of the Thames well before the Mohegans had developed close contact with Europeans, could easily have housed a population of several hundred people.”

I’m not going to give you a full history lesson here, but needless to say, accounts more recent than Baker’s offer different perspectives on what Montville was like pre-contact.

In 1645, the Mohegans were besieged by the Narragansetts on a bluff overlooking the Thames River. The Narragansetts attempted to starve them out, but Mohegan Sachem Uncas reportedly had a hunting buddy — Thomas Leffingwell, an English guy down in the Saybrook Colony, who showed up right on time (after being sent for). Leffingwell and his English crew sent beef, corn, and peas in a canoe to the fort under the cover of darkness. The Mohegans were able to flaunt their food, and show the Narragansetts that they were not nearly on the verge of being conquered. In return, the tribe sold to Leffingwell (et al.) the land that would become known as Norwich.

In 1898 the Monument to Leffingwell (pictured above) was unveiled by Uncas Gray, a descendant of Sachem Uncas. It was erected by the Colonial Dames from Fort Shantok stones and intended to resemble a cairn. It can be seen today within the burial ground at Shantok.

Fast foward to February 1925, when the Courant reported that New London County “will make a strong bid for an appropriation for a state park […]. There are three bills before the session providing for state parks in the county, one in Waterford, one in East Lyme and one in Montville. The latter, appropriating $15,000 for the purchase of the Fort Shantok site is considered as having the best chance.”

The paper does not spell this out, but Fort Shantok is taken by eminent domain in 1926. Later that year, the opening of the Fort Shantok State Park is announced. It spans 120 acres and includes what the Courant calls an “old Indian burial ground.” Thirty acres, described as an historic site, are added to the park in 1930. These are north of the village site. This area becomes a popular spot for striped bass fishing.

With the Cold War underway, United Nuclear opened its plant on Sandy Desert Road in Montville in 1959, south of Trading Cove, north of Fort Shantok State Park — because placing a nuclear facility right near a state park seemed reasonable. The factory made nuclear reactors for submarines.

Anthropologists from Columbia University, a few years later, discover the remains of the actual fort within Fort Shantok State Park. This includes three fortified walls, pits for storing grain, and both animal bones and oyster shells. You might think that this would immediately lead to better treatment of the surrounding environment. Nope.

Nearby high school students, in 1972, like others of the time, had an Ecology Club. It went on a “pollution tour” visiting various sites in the area. One of these was a stop at the Connecticut Light and Power plant on the banks of the Thames River, near Fort Shantok. Here, the students “took water temperature readings which were later fed into a computer at the plant which showed water temperature at the discharge point was 30 degrees higher than at intake,” so reported the Courant.

In April 1974, the State of Connecticut announces plans for an Indian culture museum and the addition of a boat launch at Fort Shantok State Park. Money for the museum had been earmarked as of 1969, but like many plans, it took five years for the State to get around to looking like it might act.

Within one year of that new momentum, however, the Mohegans launch a lawsuit against the State in an attempt to get Fort Shantok back, citing concerns with cemetery desecration. The wooden headstone posts were being burned by fishermen seeking warmth. Adding a boat launch would no doubt make the area more of an attraction.

By 1977, the Mohegans are looking at Fort Shantok, plus land being used by the State police barracks, Montville Correctional Institute, parts of Route 32 and Connecticut Turnpike, and a segment of the Thames River. In 1978, Connecticut claims the Mohegans waited too long to take action. Mohegans, trying to get federal recognition as a tribe, are denied their request in 1989.

In 1990, UNC Naval Products begins layoffs: about 10% of their 1000 employees are cut. By 1992, UNC Naval Products (United Nuclear Corporation) plant is in the process of being decommissioned while fulfilling a few lingering contracts; by then, there are only around 150 employees remaining. About 10% of UNC’s workforce lived in Montville. This is happening at the same time as Electric Boat is doing their layoffs. And for those who have trouble placing Montville, it’s not an easy commute to New Haven, Hartford, Providence, or Springfield.

Meanwhile, around this time, the Mohegan tribe installs Gladys Tantaquidgeon as medicine woman, with the ceremony taking place at Fort Shantok. The following year, the park becomes a National Historical Landmark. The Mohegans again go after 600 acres of State of Connecticut-owned land, including Fort Shantok.

In March 1994, the 968 member tribe receives federal status, making them Connecticut’s second federally recognized tribe after the Mashantucket Pequot. What helps them finally get this status is that they managed their burial grounds over the years, proving continuity.

The tribe’s lawyer comments, as they are still seeking those 600 acres of land, that the only non-negotiable in this is Fort Shantok, where ancestors are buried, and where they held a drumming and dancing celebration of their federal status.

The Montville area has a strong need for employment that is not driven by war. In comes gambling and entertainment. The Mohegan tribe, in May 1994, suggests a casino and theme park be built on the former United Nuclear Corp. site. Mohegan Sun (minus theme park) opens in October 1996.

After much discussion over whether or not the State can transfer land to the Mohegans, or rather, how this can happen (should then Governor Weicker be allowed to veto?), it’s reported that most of the parkland is returned to the tribe in August 1995. Melissa Fawcett, the Mohegan tribal historian, says: “It’s the first time the governor of the state of Connecticut has signed anything to the tribe instead of signing something away from the tribe.”

Yet, even in 1997 and 1998, the Courant is still writing about Shantok as if the sale never happened. Confused? Yep.

The New York Times reported that Fort Shantok was sold back to the Mohegans in 1998, and put into trust with the federal government. They are not, however, given the land. The Mohegans pay $3 million to the State of Connecticut to get the land they began suing for in 1975.

Shantok, Village of Uncas, continues to be a site for ceremonies and festivals today. The rules for use are clearly posted in more than one language. Judging from the absence of litter and ruckus, people are following them.

Fort Shantok Archaeological District — since it does not belong to the State of Connecticut, it’s not Fort Shantok State Park anymore — is located on Massapeag Side Road in Uncasville.

¹Okay, to be fair, in high school there was a Connecticut History class and one of my favorite teachers even taught a Native American history course, but I did not manage to enroll in either because I was a teenager and probably prioritized filling my schedule with study halls.

Related Posts

Standing Up

Spot the Art

Transform Distress