A postseason menorah decorates Detroit’s Cadillac Square on Boxing Day. Glass huts house nearly two dozen vendors selling everything from chocolates to vintage clothing. A larger one serves as a restaurant. Between them is a s’more station. Families skate on the nearby ice rink. The bottom floor of a building across the street has been transformed into Rainbow City, a temporary roller rink, viewable from the sidewalk. It’s cold, yet people are everywhere.

A postseason menorah decorates Detroit’s Cadillac Square on Boxing Day. Glass huts house nearly two dozen vendors selling everything from chocolates to vintage clothing. A larger one serves as a restaurant. Between them is a s’more station. Families skate on the nearby ice rink. The bottom floor of a building across the street has been transformed into Rainbow City, a temporary roller rink, viewable from the sidewalk. It’s cold, yet people are everywhere.

In Hart Plaza beside the Detroit River, visitors pose with the Monument to Joe Louis while locals jog by. A series of small parks join to form a lively riverfront. Milliken State Park features Lily Pad Lane, a boardwalk path through urban wetlands. Folks can ride walleye and egrets, among other creatures, on Cullen Plaza‘s small carousel. At least three Little Free Libraries dot the scenic walk.

Spirit Plaza behaves as a connection between the river and downtown. Spirit Plaza is where you can hear the crash of Jenga blocks coming from transparent tents that allow for social activity, even in winter. It’s where people can pose in silly plywood cut-outs and walk over pavement painted bright in geometric patterns. It was a splinter of Woodward Avenue, reclaimed for pedestrians using posts and strategically placed rocks. It’s a pilot project and temporary road closure. Its shape can change at any time.

How is this possible? Knowing that the stakes are higher when your riverfront is the first IRL impression of the United States that many will have as they cross over from Canada? Political will? Not being stifled and sullied by a risk averse industry such as that which dominates Hartford?

How is this possible? Knowing that the stakes are higher when your riverfront is the first IRL impression of the United States that many will have as they cross over from Canada? Political will? Not being stifled and sullied by a risk averse industry such as that which dominates Hartford?

In early December Fort Street Galley, an upscale food court, opened with simple, clean wooden furniture. Staff greet you upon entering unless you make a beeline to the bar. There are choices: Korean, BBQ, and more. It has evening hours. Not too cheesy of a place to take a date. The popular year-round Eastern Market just 1.5 miles away looks non-desolate after hours with help from restaurants and buildings encased in murals. A modest-sized parking lot is dedicated to market shoppers when open; spaces are up for grabs in the evening. When it’s open, the sheds host hundreds of vendors. Walking to the market is no big deal, as it’s not sited off in the urban boonies.

Besides the stuff that adds sparkle, Detroit has gotten practical. There are bike lanes in the downtown area. They have a plan for maintaining bike lanes in the winter. Under three inches of snow, the bicycle lanes get salted while 3-6″ means snow removal and salting. Beyond that amount, bike lanes will still be plowed, but after vehicle lanes are given attention. It’s not perfect, but it’s a plan.

Besides the stuff that adds sparkle, Detroit has gotten practical. There are bike lanes in the downtown area. They have a plan for maintaining bike lanes in the winter. Under three inches of snow, the bicycle lanes get salted while 3-6″ means snow removal and salting. Beyond that amount, bike lanes will still be plowed, but after vehicle lanes are given attention. It’s not perfect, but it’s a plan.

How is this possible in a city that famously declared bankruptcy? Locals will say that the billionaire CEO of Quicken Loans has Detroit in his hands. Be that as it may, the investment shows. There are critics of the pace of progress in Detroit; those are fair observations, but I wonder what these same folks would have to say about the rate of change here in Hartford.

Detroit is visibly working out its shit in a way that Hartford isn’t.

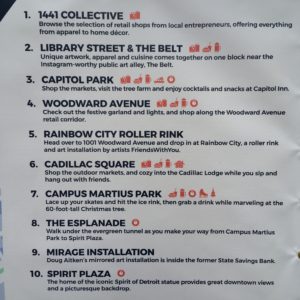

Toledo, quieter than a mouse, also manages to get a few things right. The Toledo Mud Hens stadium is scaled as to not glare with ego. It fits neatly into the neighborhood where visitors can easily find pubs and moderately-priced restaurants, which also are within several short blocks of where the Walleyes play. Though minor league sports are never a major driver of economic activity, the approach taken in Toledo feels as if it is in touch with the city’s reality. As a visitor, you get the sense that baseball and hockey are there for family enjoyment, rather than as a last ditch effort to save the city’s finances.

Toledo, quieter than a mouse, also manages to get a few things right. The Toledo Mud Hens stadium is scaled as to not glare with ego. It fits neatly into the neighborhood where visitors can easily find pubs and moderately-priced restaurants, which also are within several short blocks of where the Walleyes play. Though minor league sports are never a major driver of economic activity, the approach taken in Toledo feels as if it is in touch with the city’s reality. As a visitor, you get the sense that baseball and hockey are there for family enjoyment, rather than as a last ditch effort to save the city’s finances.

In the downtown, the pedestrian signal is included in the light cycle — no need to press a button to beg permission to cross the street. Bicycle infrastructure has room for growth, but there is at least one protected bike lane. People are pushing back against backwards transportation designs. There is a dog park.

How? Political will? Engaged businesses like Owens Corning and ProMedica?

How? Political will? Engaged businesses like Owens Corning and ProMedica?

Over in Indianapolis, the Monon Trail spans ten miles, connecting neighborhoods to the downtown. Housing, restaurants, and retail line the bike path. Being able to safely bike to a Chipotle with minimal interaction between bicycle and motorized vehicle is not merely the stuff of fantasy in Indianapolis.

There are cultural differences that are hard to explain, but west of, say, the New York state border, the landscape becomes cleaner. . . rural, suburbs, and cities. Neither Detroit nor Toledo nor Indianapolis appeared to have more trashcans in their downtown areas than Hartford, but both were tremendously cleaner. It is no exaggeration to say that I did not see as much as a cigarette butt, and that includes Toledo’s industrial section and the edges of Detroit’s downtown where people panhandled. Detroit’s trash cans indicated the presence of a BID, yet they were not even as visibly active as in Hartford. At no point in the Midwest did I need to walk in the street to skirt around a ditched sofa or massive pile of trash.

What gives? Our mayor came out on the right side of things by denouncing any attempt to convert the North Meadows bird sanctuary to an active trash dump. That this was even a discussion should be shocking. Here we are, unable to manage our waste when Connecticut should be far beyond other regions when it comes to livability. Hartford’s struggles are human-created problems, all fixable. We need to see more than sporadic leadership, creativity, and urgency to move forward. Will 2019 be the year that we ditch the steady habits that no longer serve us?

Lessons from Mid-Afar

In Hart Plaza beside the Detroit River, visitors pose with the Monument to Joe Louis while locals jog by. A series of small parks join to form a lively riverfront. Milliken State Park features Lily Pad Lane, a boardwalk path through urban wetlands. Folks can ride walleye and egrets, among other creatures, on Cullen Plaza‘s small carousel. At least three Little Free Libraries dot the scenic walk.

Spirit Plaza behaves as a connection between the river and downtown. Spirit Plaza is where you can hear the crash of Jenga blocks coming from transparent tents that allow for social activity, even in winter. It’s where people can pose in silly plywood cut-outs and walk over pavement painted bright in geometric patterns. It was a splinter of Woodward Avenue, reclaimed for pedestrians using posts and strategically placed rocks. It’s a pilot project and temporary road closure. Its shape can change at any time.

In early December Fort Street Galley, an upscale food court, opened with simple, clean wooden furniture. Staff greet you upon entering unless you make a beeline to the bar. There are choices: Korean, BBQ, and more. It has evening hours. Not too cheesy of a place to take a date. The popular year-round Eastern Market just 1.5 miles away looks non-desolate after hours with help from restaurants and buildings encased in murals. A modest-sized parking lot is dedicated to market shoppers when open; spaces are up for grabs in the evening. When it’s open, the sheds host hundreds of vendors. Walking to the market is no big deal, as it’s not sited off in the urban boonies.

How is this possible in a city that famously declared bankruptcy? Locals will say that the billionaire CEO of Quicken Loans has Detroit in his hands. Be that as it may, the investment shows. There are critics of the pace of progress in Detroit; those are fair observations, but I wonder what these same folks would have to say about the rate of change here in Hartford.

Detroit is visibly working out its shit in a way that Hartford isn’t.

In the downtown, the pedestrian signal is included in the light cycle — no need to press a button to beg permission to cross the street. Bicycle infrastructure has room for growth, but there is at least one protected bike lane. People are pushing back against backwards transportation designs. There is a dog park.

Over in Indianapolis, the Monon Trail spans ten miles, connecting neighborhoods to the downtown. Housing, restaurants, and retail line the bike path. Being able to safely bike to a Chipotle with minimal interaction between bicycle and motorized vehicle is not merely the stuff of fantasy in Indianapolis.

There are cultural differences that are hard to explain, but west of, say, the New York state border, the landscape becomes cleaner. . . rural, suburbs, and cities. Neither Detroit nor Toledo nor Indianapolis appeared to have more trashcans in their downtown areas than Hartford, but both were tremendously cleaner. It is no exaggeration to say that I did not see as much as a cigarette butt, and that includes Toledo’s industrial section and the edges of Detroit’s downtown where people panhandled. Detroit’s trash cans indicated the presence of a BID, yet they were not even as visibly active as in Hartford. At no point in the Midwest did I need to walk in the street to skirt around a ditched sofa or massive pile of trash.

What gives? Our mayor came out on the right side of things by denouncing any attempt to convert the North Meadows bird sanctuary to an active trash dump. That this was even a discussion should be shocking. Here we are, unable to manage our waste when Connecticut should be far beyond other regions when it comes to livability. Hartford’s struggles are human-created problems, all fixable. We need to see more than sporadic leadership, creativity, and urgency to move forward. Will 2019 be the year that we ditch the steady habits that no longer serve us?

Related Posts

In Your Neighborhood: Clay Arsenal/Upper Albany

An Urban Move: No Gas Required

Look: Downtown North